by | Liz Alexander, PhD Futurist. Author. Consultant. Speaker.

Dr. Liz Alexander has been named one of the world’s top female futurists. She combines futures thinking with over 30 years’ communications expertise to produce publications that showcase the advice of fellow futurists on issues including the future of education, and how businesses can practically benefit from working with the futures community.

Dr. Liz is the author/co-author of 22 nonfiction books published worldwide, that have reached a million global readers, and has contributed to leading US technology magazine Fast Company, Psychology Today, and journals such as Knowledge Futures, and World Futures Review. She earned her PhD in Educational Psychology at The University of Texas at Austin.

How does your working day look so far?

I imagine you are in your fully functioning home office where digitisation has replaced every scrap of paper. Everything you need, including your robotic personal assistant, is available at the swipe of a finger. Or perhaps you are carrying out your job from a beach in, say, Tahiti. At the very least, you have relocated to what Aldous Huxley, the author of Brave New World, once envisaged: One of those “small country communities, where life is cheaper, pleasanter, and more genuinely human than… the great metropolitan centres of today.”

No? Not even close?

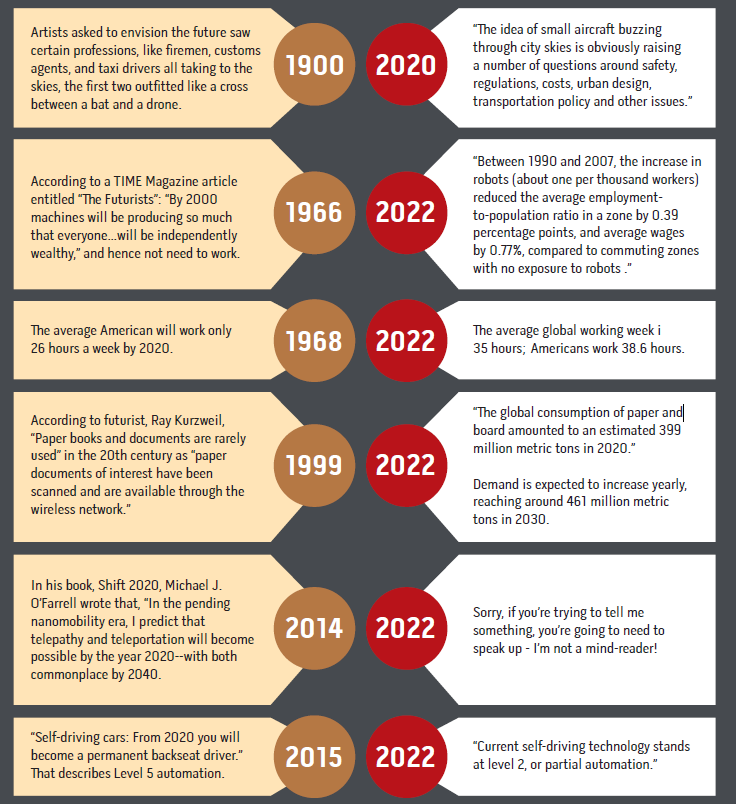

Yet this is what future thinkers of yesteryear imagined we would experience in 2022. And these aren’t even some of the more outlandish suggestions that have been made about the future of work over the past 100 years (See Boxout).

Perhaps it is time we asked ourselves: Why is it that so many predictions about the future of work are just plain wrong? Why, for example, did a highly publicised University of Oxford study from 2013 confidently state that “47 percent of US jobs were at high risk of being automated within two decades,” when just three years later the figure was estimated to be closer to 9 percent?

Why do we fail to question a future in which autonomous trucks will put tens of millions of drivers out of work worldwide, when the reality–at least according to someone who has studied the phenomenon–is that: “Trucking and delivery includes a lot of skills and tasks that are probably going to be very hard to automate? ”More to the point, what can we learn from these past biases and mental blocks, in order to avoid repeating them?

Psychology First

Allow me to segue into that by pointing out how often decision-makers appear to ignore the importance of work for the psychological health and wellbeing of the vast majority of ordinary people.

Countless international studies have shown that the loss of jobs is associated with a range of mental health issues, from apathy and depression, to substance abuse and the decline of family relationships.

Where high unemployment occurs across communities, this is associated with a rise in violence and criminal behaviour.

Why, then, would those who help shape our future appear so enthusiastic about (or accepting of?) a world in which robots take all the jobs and we humans are largely left to navigate life without any sense of well-being, individual satisfaction, or accomplishment? Let alone where the money to live is going to come from.

Thankfully, that scenario is unlikely to come to pass.

Yet that brings me to my first point, about the hubris inherent in much of our future thinking concerning the world of work. I have written on several occasions about how prominent business leaders frequently try to sell us visions of futures that are tied largely to their own commercial advantages (see for example, my Fast Company article entitled: What Faux Futurists Cost the Rest of Us). Just because someone is seen as smart, passionate, and a “visionary” it doesn’t mean that their pronouncements are right. Elon Musk is a prime example. According to Tesla employees’ testimony to the California Department of Motor Vehicles in 2021, “Tesla CEO Elon Musk’s messaging around driverless vehicle technology does not always ‘match engineering reality’.”

No matter how brilliant or well-educated a person might be: “Combining exponential change with multivariate phenomena two things humans are bad at estimating and understanding is a challenging analytical problem. That’s why futurists are so often wrong: There are too many variables and unknown feedback and feedforward loops.”

When their feet are being held to the fire by impatient stakeholders, decision-makers tend to want future-focused outcomes that are quickly arrived at, neatly packaged, and cut-and-dried.

After all, who wants to grapple with uncertainty when you are responsible for determining how the future will affect your constituency?

But if we are not willing to take the time and considerable mental effort to work through a range of scenarios not least the “worst case” examples–then it is hardly surprising that so many variables and loops are overlooked.

Giving Attention to the Wrong People?

Another reason why predictions about the future of work tend to be so inaccurate, at least in my opinion, is that we focus too much time and attention on those who are over-confident about what the future of work will look like, and how soon it will appear.

As Bill Gates was quoted as saying, “We always overestimate the change that will occur in the next two years and underestimate the change that will occur in the next ten.”

But when, in all that time, does anyone ever ask the people who will be affected by these changes about how, where, and when they want to work?

As one report backed by the London School of Economics entitled ‘Unlocking Opportunities for People Hard Hit by Automation and Globalization’ recommends: “We should spend less time trying to predict the future of work and more time focusing on what workers really want from work.”

As a futurist this makes total sense to me, given that we know the future is fluid and shaped by the decisions and actions we take in the present.

Configure work according to human needs, not just technological drivers, and we will create the future people want, rather than presenting them with forecasts they will likely fight against.

After all, we have plenty of examples where human behaviour trumps technological pronouncements:

Human Choice Trumps Technology

• E-books were expected to threaten the physical book with extinction. Even in 2016 a BBC.com article proclaimed that this vision, “is well on its way to being realised”. In 2022, e-books didn’t even come close since a considerably higher percentage of people still buy printed books rather than ebooks .

• In 2005, The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology posited that by now we would be ingesting “nanobots,” making traditional food consumption “obsolete.” Yet TV shows and YouTube about cooking and eating are increasing in popularity worldwide. A meal-in-a-pill, or even a nanobot, might fit “abstract notions of technological efficiency and scientific notions of health ,” but those aren’t why people are enjoying cooking, and eating, real food.

• In Shift 2020, one “global trends expert” predicted that robots would become our therapists and home care assistants. Yet such pronouncements glibly overlook concerns raised by one study entitled, ‘Caregivers’ use of robots and their effect on work environment: “We know little about robots’ long-term effects on working life. Also missing is research about legal and ethical aspects of using robots, not just in regard to patients’ and clients’ integrity and safety but also to employees.”

In short, predictions about the future–not least the world of work which provides many human beings with a sense of esteem, satisfaction, and accomplishment– invariably ignore human psychology. They also highlight the fact that we have a tendency to become over-excited by the latest technological advancements without thinking deeply about their social, even ethical, ramifications.

Data ≠ Futures Thinking

Which brings me to one more forecast that I don’t see bearing fruit any time soon; another example of how technologists get things wildly wrong.

In 2012 the chief futurist for Cisco Visual Networking believed that in less than a decade. there would be no need for futurists because, “everyone would be able to predict the future themselves.”

He ascribed the universal adoption of this skill to the “rich source of data, creating unprecedented insight.” As if access to “cloud-based tools” alone would enable widespread “what-if” analysis and transform people into futures thinkers.

As with so many highly-educated, smart individuals, this man made the mistake of thinking that if you provide people with a certain environment, they will suddenly think, act, and achieve in the ways you expect.

That isn’t reality, it’s wishful thinking.

As the Director of the Institute for the Study of Political Economy at Ball State University in the United States, Professor Steven Horwitz points out, “Rather than focusing on the big, dramatic technologies and what seem to be their efficiency-enhancing elements, predictors of the future should be thinking more about the everyday things that matter to human beings and trying to imagine how technological change might interact with commerce and culture to produce the weird but still recognizable future.”

Could it be that we get the future of work so wrong because we’re trying to fit complex, unpredictable human beings into scenarios that hold no appeal for them?

Should we not try to better understand what people want from their working lives–and then help them create futures that are more, in Aldous Huxley’s words, “genuinely human.”

Otherwise the future of work that we posit today will never become a reality, but remain an over-enthusiastic elitist dream.

Imagination vs Reality

References