by | Leah Soroka, B.Comm. M.Sc., Director, S&T Foresight and Science Promotion, Division Science Policy Directorate of Health Canada | Lois Macklin, B.Sc., M.A., Ph.D., Principal Business Advisor-Foresight, Alberta Innovates-Technology Futures

In Canada, a federal government department and a provincially owned research corporation have collaboratively implemented a major foresight initiative designed to anticipate future challenges and opportunities related to improving the health status of Canadians in a single generation (to 2030).

The premise underpinning the project design was that simply conducting foresight activities is often insufficient to effect forward looking decisions or behavioural change.

Foresight activities must be designed with the intent to take action. This paper focuses on the cumulative learnings about how to deliver foresight insights to key decision makers in a way that impacts present day decisions. The following is a summary of the key learnings from the Health Foresight Initiative that the authors consider useful contributions to the field of foresight.

1) Deep understanding of emergent complex issues takes multiple conversations spread over a sufficient period of time to allow reflection.

Several iterations of the large and small engagement sequence are required to achieve a deeper understanding of the forces and factors at play and how they interrelate. Arriving at recommendations that result in the implementation of complex adaptive management responses may require several months of ongoing work and provocative discussion.

2) Workshops that engage larger numbers of participants typically make only incremental contributions to current knowledge.

Large group events surface a plethora of ideas and perspectives but rarely generate more than incremental advances in thinking.

3)Highly innovative thinking is best done by small groups of high intensity creatives.

Certain dynamic thinkers have an innate ability to “reperceive” and challenge deeply held assumptions. They produce the best work in small group settings but make valuable contributions in large groups through the introduction of provocative ideas.

4) Decision makers must be engaged both intellectually and emotionally.

The presentation of foresight findings in the form of a well-written rationale and strategic plan is not necessarily sufficient to ensure consideration by decision makers. Emotional connectivity must be established through the use of provocative engagement processes and multiple media (e.g., video, music, and voice) reporting and communication mechanisms.

5) The leadership of a major foresight project requires a complex and unique set of skills.

More than good management skills are required to design, organize and execute a major foresight event. The responsibility requires a unique combination of leadership, abstract thinking, experimentation and organizational abilities that has yet to be fully appreciated by many who commission foresight projects.

6)Development of a cascading communications strategy is critical for presentation of foresight findings to key decision makers.

Frequent cascading communications tailored to targeted decision makers expands the capacity of the recipients to embrace new ideas and commit to action.

• At the time of this writing, the insights and findings of the Health Foresight Initiative are being linked to key strategic decision making and planning processes within both participating organizations. At Health Canada, a set of recommendations for short, medium and longer term actions that will provide both quick results and business continuity have been presented through a series of presentations and publications. Alberta Innovates-Technology Futures has incorporated the findings into a corporate Health Research and Investment Strategy for consideration by the Board of Directors.

1. Introduction

Between December 2009 and March 2011, a major collaborative foresight initiative was undertaken by the Science and Technology Foresight Policy Division of Health Canada (a federal government department) and Alberta Innovates-Technology Futures (a provincially owned research institution). The project (referred to in this paper as the Health Foresight Initiative) involved the implementation of an iterative multifaceted foresight process to gain new insights and understanding about science and technology investments that could be taken today, which would contribute to improving the health of Canadians in a single generation (to 2030). The Health Foresight Initiative was conceptualized and designed to overcome the challenges related to translating the knowledge and insights gained from foresight activities into tangible recommendations that result in actionable decisions. Within the context of government bureaucracies, powerful system-level impediments make the utilization of foresight findings for the purposes of public policy development difficult. In the demanding milieu of the of the public service, these constraints can limit the efficacy of foresight as a decision making tool (Macklin, 2010). This paper is a report on the work of the Health Foresight Initiative. It explores the source of impediments to translating foresight insights into action and then goes on to describe the design considerations employed during the Initiative to overcome these real or perceived barriers. By presenting this case study, the authors hope to make a valuable contribution to a void in the literature related to linking foresight to actionable decisions.

1.1 Why It Is Difficult To Link Foresight to Action

Many organizations, including government, increasingly recognize the value of longterm thinking to inform strategic planning processes. However, a review of foresight literature indicates that the generation of new ideas and insights through strategic conversations is insufficient to lead to action. In part, this may be due to the challenges of making decisions in the face of complexity, but it is also related to a perception by senior decision makers of risk and being overwhelmed. Acting upon these ideas and insights often requires significant system level transformations that challenge traditional approaches and decision making processes.

Research shows that human decision making in any complex context is difficult (Brehmer, 1992; Chermack, 2004; Dorner, 1996). Brehmer (1992) suggests that decision making in such contexts is often complicated by:

1) the requirement for a series of decisions rather than a single decision,

2) interdependence; in that current decisions constrain future decisions,

3) an environment that changes as a result of decisions made, and

4) the need for critical timing and correct ordering.

Furthermore, differing space and time perspectives may be expected to impact decision making by bringing different approaches and priorities (Slaughter, 1993). In the realm of public service, decision making is particularly complex. To start with, every public policy has three key elements: problem definition, the setting of goals and outcomes, and the choice of policy instrument whereby those goals are achieved and the problems addressed (Pal, 2006). The choice of policy instruments must facilitate achievement of the desired goals and outcomes. Furthermore, horizontal alignment is required with other policy agendas that exist at the regional, national, and international level. Development of each element occurs at a different stage of the public policy making process and is in itself complex. Consequently, the more multifaceted the issue the more difficult it is to define the problems, set policy goals and make decisions about how to achieve the desired goals. This difficulty is particularly exacerbated when decisions made in the present must accommodate the changes and uncertainty that occur over long periods of time. The complexity of undertaking decisions in the public arena is further compounded by the capricious nature of politics. There is an expectation for a high degree of certainty that generally cannot be found when addressing such complex issues, which makes it very difficult for decision makers in the public service to undertake proactive decisions without incurring political risk. Increasing public scrutiny combined with the short electoral cycle means that elected officials are highly incented to deliver short term goods and benefits and delay the imposition of costs (Pal, 2006). “Generatively complex problems” (Kahane, 2004) that require sacrifice now for the delivery of benefits beyond the boundaries of the electoral cycle, present a politically unpalatable decision making dilemma.

Chermack (2004) identifies two other overarching categories of decision failure:

1) simple explainable error or mistake and

2) when the unusual happens and the guiding cognitive map and mental model is rendered obsolete.

The first category denotes the statistical reality that some error is inevitable. Failure of the cognitive map occurs when it becomes difficult for an individual to articulate what the environment requires because a system level discontinuity has occurred, making their mental model obsolete. Chermack (2004) describes the tendency of decision makers to either ignore or underestimate the contribution of disruptive internal and external systemic elements. Instead, decisions are often based upon by habit, conformity, social pressure, or personal interest.

The literature also asserts that the key to improving decision making and ultimately improving outcomes lies in changing or altering current mental models (Senge, 1990; Chermack, 2004; van der Heijden, 2005). As the clock speed of change increases and the decision making context becomes more complex and dynamic, the re-calibration of existing mental models becomes essential for good decision making. Wack (1985) stated that in order to operate in an uncertain world people needed a way to “reperceive” and question their assumptions about the way the world works, thereby changing the current decision making premise.

Despite the growing body of opinion that foresight activities can lead to the implementation of different (and ideally improved) courses of action, many key decision makers are still reluctant to incorporate foresight findings into their decision making processes. The foresight work described in this case study was undertaken as a means to help leadership “reperceive” the future of health and understand the forces and factors impacting the wellness of the next generation of Canadians. The Health Foresight Initiative was consciously designed and communicated so that senior decision makers in government can comfortably utilize the information generated to inform decisions about the future direction of health policy and related investments.

2. The Health Foresight Initiative Case Study

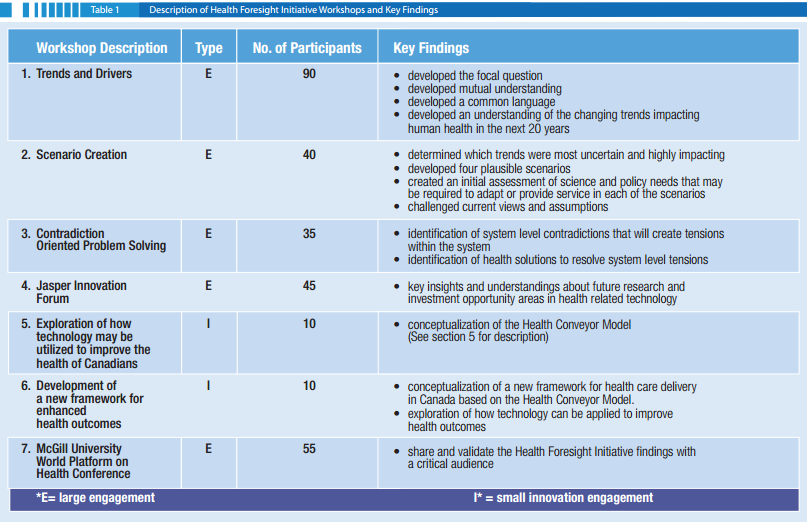

The Health Foresight Initiative involved the implementation of an iterative multi-faceted foresight process to gain new insight and understanding about how to improve the health of Canadians in a single generation. More specifically, the goal was to inform both lead organizations about innovative science and technology investments that could be made today that would improve population health outcomes in the future. The Initiative involved approximately 250 stakeholders and professionals from the Canadian health sector. Project events were held in Ottawa, Ontario, Jasper, Alberta, and Montreal, Quebec. Table 1 presents the series of workshops that comprised the Health Foresight Initiative and their respective outcomes. Pertinent to the interpretation of the table is the labelling of events as either Engagement (E) or Innovation (I). Engagement events were characterized as being larger in nature and involving a multidisciplinary group of stakeholders mainly drawn from the health sector. Engagement events were designed to foster an understanding of the complexity of the issue, surface a variety of perspectives and ideas, and extend current avenues of dialogue as they relate to the future health of Canadians. The engagement events were particularly effective at creating mutual understanding and developing a common language amongst diverse stakeholders.

The innovative events involved a smaller number of highly innovative thinkers (see section on participant selection). These events were designed to challenge conventional opinion and push current thinking about how to improve health outcomes into uncharted territory. The ideas that surfaced were intended to be provocative and disruptive in nature and were used to stimulate new dialogue in the broader audiences of the engagement events and the health sector in general.

During the execution of the 16 month initiative, the project leaders also drew upon external sources of ideas and inspiration such as health sector meetings, publications, and conferences. Of particular significance was a conference hosted by the Institute for the Future Science and Technology Foresight in Palo Alto, California, USA. Participation in this event resulted in the identification of 16 specific science and technology advancements that could enhance human health. These findings were introduced into the Health Foresight Initiative dialogue for validation and consideration.

The last event of the Health Foresight Initiative at the McGill University World Platform Conference on Health, concluded on March 17, 2011. As of the writing of this paper, Health Canada and Alberta Innovates

Technology Futures are in the process of developing key recommendations for presentation to executive within their respective organizations. Communication of these recommendations is expected throughout 2011 and 2012.

3. Methodology

Simply conducting foresight activities is often insufficient to affect forward looking decisions or behavioural change. It was the thesis of the project leaders that by recognizing the challenges faced by decision makers and designing the process in response, the efficacy of the Health Foresight Initiative would be significantly enhanced. Key design considerations for linking foresight to action included:

1) project leadership

2) design of the process

3) designing for engagement

4) designing for innovation

5) designing for communications

Consideration of these five aspects was essential to derive good foresight insights and empower transformational decisions related to the application of science and technology for improving human health.

3.1 Project Leadership

In the authors’ opinion, the competencies required to execute a successful foresight project are worth noting here. They extend well beyond simple project management to include the ability to lead a diverse group of people through often highly sensitive conversations and then deliver provocative and potentially disruptive findings to an often less than receptive audience of decision makers who may be deeply uncomfortable questioning embedded assumptions about the future.

Like many other high level deliberative processes, addressing the future requires strong communication skills, the ability to multitask, creative thinking and the flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances including resource availability. Leaders of major foresight initiatives must apply the tools of complex adaptive management (Porter & Kramer, 2011). This approach entails an understanding of the benefits of planning accompanied by the flexibility to maintain the focus on the future, make mid-course corrections to fulfill the project objectives and respond to new information and developments as they arise.

Despite the fact that most foresight projects typically have common elements (diverse stakeholders, collaborative engagement, etc.), a depth of experience and knowledge is required to choose foresight methods appropriate to the organizational context and the issue at hand. It is essential that leaders of foresight work have the ability to think critically about the way the future is described and develop innovative linkages to present day realities. Foresight is in itself, a disruptive technology. Thinking about a radically different future than has been complacently assumed, challenges people and organizations at profoundly deep levels. Furthermore, there is a delicate balance and potential tension between pervayers of convential wisdom who have invested interests in maintaining the status quo and the attributes of emergent new systems that may be described during the foresight process.

In order to maintain the commitment of participants to the foresight process it is necessary to build an environment of trust. Skill is required to negotiate highly sensitive conversations that challenge deeply embedded assumptions and mental models about the future. To provide participants with the level of comfort and safety needed for such open and frank conversations, all events of the Health Foresight Initiative were conducted under Chatham House Rule, which granted anonymity in written reports and conversations or presentations conducted outside the workshops.

3.2 Design of the Process

The design of the Health Foresight Initiative involved a complex set of considerations to increase the likelihood of the findings being converted to action. These included:

• defining the focal question,

• choice of foresight methodologies,

• size of the workshops and facilitation,

• budget and logistics

• choice of participants, and

• the communication strategy

3.2.1 Defining the Focal Question

The cornerstone of any foresight initiative is the focal question. A well-conceived focal question sets the tone and scope of the entire foresight initiative. If the focal question fails to convey the appropriate information, the ensuing conversation may fail in depth, scope and organizational relevance. The focal question in this case study explored “How to improve the health of Canadian’s by 2030 (in a single generation)”. It was designed to ensure a full exploration of the forces and factors that are affecting the health of the Canadian population now and into the future. Current health sector dialogues in Canada are dominated by discussions about the sustainability of the publicly funded health care system. It was a major challenge for the project leaders to move the discussions of the Health Foresight Initiative beyond this present-day anxiety. The focal question was carefully phrased to encourage consideration of the current Canadian health care system as only one of a suite of factors that can contribute to improving the health of Canadians. By referring to a single generation, the focal question implicitly encouraged participants to think about maintaining life-long health rather than how effective the health system is at curing those who are ill. Other key requirements were that the focal question:

• was an open-ended yet focused inquiry;

• did not suggest or lead to a specific “right” answer;

• contained emotive force and was intellectually stimulating;

• was succinct but challenging; and

• was relevant to the participants involved.

3.2.2 The Choice of Foresight Methodologies

The choice of foresight methodology employed at each workshop was guided by the the cumulative findings from previous workshops and the level of engagement appropriate for the participants invited. The workshops were consciously designed to move participants out of their comfort zone, which often provokes emotional response. This was important because emotive moments often signal that participants are in the process of recalibarting their mental models. The Health Foresight Initiative involved the organization of seven different workshops (See Table 1). The strategic design considerations for each are discussed below.

1) Trends and Drivers Workshop

The Trends and Drivers workshop was the introductory event of the Health Foresight Initiative. This was an exploratory exercise, the purpose of which was to vet the topic with stakeholders in the health sector and begin to build a common language and understanding about the forces and factors that would be impacting the health sector and by default, the health of Canadians, in the longer-term.

2) Scenario Creation Workshop

The Scenario Creation Workshop was a foundational piece of work in the Health Foresight Initiative. The purpose of this workshop was to challenge the deeply embedded assumptions that exist in the Canadian health sector about current health care delivery and how the future health outcomes of Canadians may be impacted by technology. Using the trends and drivers identified in workshop one, four distinct but linked narratives were created about the health of Canadians in 2030. The process of creating these narratives served to build solidity amongst the participants about the challenges to be addressed if the health outcomes of the Canadian population are to improve over the next twenty years. In addition, the scenarios provided an opportunity to test current strategies and discuss possible adaptive management responses against a range of possible future outcomes. Achieving this allegorical understanding was useful as it validated the relevance of the focal question and forced preliminary exploration of disruptive or transformational solution sets.

3) Contradiction-Oriented Problem Solving Workshop

Contradiction-oriented problem solving is focused on finding fundamental contradictions within a system, identifying the core problems, and finding innovative solution sets by applying experiential knowledge. The intent was to examine how science and technology can enable a response to current and future challenges. The approach is based upon the work of Russian scientist, Genrikh Altshuller(1984). This approach was chosen for the third workshop of the Health Foresight initiative because project leaders recognized that foresight events need to stimulate conversations and debates about various dimensions of the problem. The scenarios created in workshop two were used as the basis for identifying emerging tensions within the Canadian health system. The workshop was intended to bring about moments of creative tension as it is through this tension that individuals often become aware of the need for action.

4) The Jasper Innovation Forum

The Jasper Innovation Forum engaged an entirely new group of participants. At this workshop, the conversation was purposely focused on improving child and maternal health. The objective was to produce a set of general recommendations for future areas of technology research investment. Participants were broken into groups and tasked with answering specific questions (drafted by the project leaders) about the role of technology in improving future health outcomes for Canadians. Opportunity was provided for presentations by each of the groups followed by a plenary discussion of the implications of those findings for improving the Health of Canadians.

5) Workshop on How Technology May Improve the Health of Canadians

The first four workshops of the Health Foresight Initiative were all large engagement processes. While each surfaced many ideas, the level of innovation that emerged was only incremental and to some degree, repetitive between events. To move beyond this plateau a group of ten highly innovative thinkers were invited to a one day brainstorming session. The purpose of this workshop was to synthesis the dialogue from the previous events, focus on the most salient findings and apply them in an innovative way to the focal question. The result of this work was the conceptualization of a completely new model of health needs assessment called the Health Conveyor Model.

6) Workshop on the Development of a Technology Supported Framework for Enhanced Health Outcomes in Canada

The sixth workshop of the Health Foresight Initiative reassembled six of the ten people involved in workshop five, plus four new participants. This was an intense and fluid two day discussion focused specifically on the identification of technologies required to empower individuals to take control of their own health and enable caregivers to support those who are unwilling or unable to help themselves. This workshop was a watershed event. It represented the first time that the conversation shifted to discussion of what an emergent new health delivery system might be like, as opposed to the previous focus on extensions of the status quo. The work resulted in the articulation of a new framework for enhancing the health of Canadians and an understanding of how deployment of sensors and web-based technologies could positively impact the management of five chronic conditions including obesity, mental health, diabetes, aging and cancer.

7) Workshop at the McGill University World Platform Conference on Health

The purpose of holding the seventh work shop as part of a McGill University conference was to present a new approach to improving health outcomes that recognizes self-empowering technologies as essential tools for maintaining the lifelong health and wellness of Canadians. By inviting comments from a critical audience of academics and health professionals in the prestigious setting of McGill University, the recommendations that emerge from the Health Foresight Initiative have enhanced credibility.

3.2.3 Size of the Workshops and Facilitation

One of the hard but crucial aspects of a foresight process is to find ways of thinking about systemic change and questioning current assumptions. This requires a careful sequencing and comparison of disruptive ideas with current assumptions. During the Health Foresight Initiative two types of workshops were strategically employed; large engagement events that promoted incremental advances in current thinking and smaller high intensity events intended to developed disruptive and provocative new ideas. By combining the two types of events, the depth and complexity of the ideas generated was increased and the probability of consideration of those ideas by key decision makers was enhanced. Professional facilitators were hired for all the workshops of the Health Foresight Initiative but they played a much subtler role in the innovation workshops so that fluid spontaneity was not lost.

3.2.4 Budget and Logistics

Collaboration between Health Canada and Alberta Innovates-Technology Futures leveraged the leadership experience and financial contributions of each organization. The combined budget was sufficient to afford the hosting of the workshops in various locations across the country, which created the opportunity to involve a greater number of participants and incorporate a broader spectrum of expertise and knowledge. The large engagement processes were the most costly events of the Initiative because they occasionally required paying for participant travel, and required more staff time, hospitality costs, and the rental of event facilities.

3.2.5 Selecting Participants

The choice of participants at each stage of the Health Foresight Initiative required careful consideration on the part of the project leaders. Depending upon the size and purpose of the workshop, different knowledge sets and capacities were required. For that reason participation at all events was by invitation only.

The largest events were the Trends and Drivers workshop, the Scenario Creation workshop, the Jasper Innovation Forum, and the workshop at the McGill University World Platform Conference on Health. The project leaders felt that in these large engagements the best work would be done by participants who had strong competencies in integrating and synthesizing knowledge from a number of disciplines, had good analytic skills, and who were skilled in inter-personal collaboration and communication. To minimize the chance of group bias, it was important to assemble a multidisciplinary group of participants who could bring a variety of knowledge and perspectives to the conversation. To create the appropriate balance of positions and ideas, a mix of subject-matter experts, innovative thinkers and creatives was selected. Special effort was made to solicit participation from the arts, civil society, the humanities, and other non-health related disciplines. A crucial requirement of all participants was that they exhibit an ability to question their own assumptions and suspend disbelief.

Several of the participants in the large engagement events were people of influence in the health sector and who were senior decision makers within their respective organizations.

These individuals had the greatest potential for translating new insights and knowledge gained from the foresight work into tangible present-day decisions and actions. Furthermore, they raised the profile of the initiative and could influence the thinking of others who did not participate. The project leaders considered the inclusion of key decision makers in the large events as crucial to ensuring broader acceptance and ultimately careful consideration of the findings for decision making and strategic planning purposes.

Project leaders also made special effort to attract several individuals who are uniquely suited to doing foresight work. The fondly dubbed title of “wing-nut” (Soroka, 2010 personal communication) was given to this type of participant for their uncanny ability to deal with dialectics and multiple solution sets, critical thinking skills, and propensity to generate provocative new ideas. These hyper-innovators have a habit of looking for new ideas and information, not just in their field and areas of focus but also across many other disciplines. They have an innate ability to make abstract linkages in ways that quickly challenge the status quo and advance current thinking. Because they were often the source of radical new ideas, inclusion of these “remarkable people” (Schwartz, 1991) in the large engagement events provided important intellectual stimulation. In the smaller innovation workshops, the ability of these participants to navigate complex systems, creatively link concepts, and then translate this new knowledge into actionable recommendations was of paramount importance.

3.3 Designing for Engagement

The large engagement events of the Health Foresight Initiative were characterized as facilitated workshops typically involving over 40 diverse stakeholders. Large amounts of ideas and dialogue were generated at the engagement workshops. Participants tended to be deeply knowledgeable individuals with the ability to recognize a good idea, adapt it, and implement it if they desire. An understanding of the complexity of the issue was forced by preventing premature consensus through the exploration of second and third order consequences. The expectation was that participation in the engagement workshops would expose a large number of influential people to a plethora of perspectives and ideas that originated outside their respective areas of responsibility and expertise. This exposure would challenge their current assumptions about the forces and factors that could impact population health by 2030 and build anticipation for release of the Initiative findings and recommendations.

3.3.1 Designing for Innovation

Small groups of highly motivated people are often most able to generate radical new ideas. Consequently, participation in the two smallest workshops of the Health Foresight Initiative was purposely restricted to ten people, many of whom were drawn from the pool of hyper-innovators. These innovation workshops were designed to be intense and creative exchanges that consolidated previous dialogue into innovative new concepts. The purpose of both was to synthesize highly innovative policy and investment recommendations from the dialogue of the first four events.

3.3.2 Designing for Communication

From the onset, project leaders recognized the need for a determined communication strategy targeted at senior executives, health industry leaders and strategic partners. Drawing from the field of knowledge management, a “cascading” (Snowden, 2010) communication strategy was developed that entailed ongoing presentations about the progress and findings of the Health Foresight Initiative. It was based upon the premise that it is easier to introduce new ideas gradually, versus a mass delivery all at once. This type of “cascading” communication is intended to expand the recipient’s zone of proximal development (expansion of thought from one’s initial position). The premise being that gradual uptake and expansion of understanding allows time for reflection and absorption of new concepts, building the receptor capacity of the target audience. Deployment of a cascading communication approach was very effective at maintaining the profile of the event over a 16 month period and building anticipation for the project recommendations amongst key decision makers.

An early step of the communication strategy was definition of specific communications parameters for targeted decision makers. Analysis of their thinking process, language used, motivators, past actions, and case studies where they were inspired to act allowed articulation of the foresight findings in terms relevant to that decision maker’s context. A report was generated upon completion of each workshop, accompanied by a number of other tailored communication tools such as briefing notes, concept papers and power- point presentations. Short video presentations were created of the four scenario narratives generated in workshop 2. Through the use of music, images and voice decision makers were emotionally engaged in these fictional futures in a way not possible through the written word.

A second communication consideration was related to participant engagement. The ability to attract the right participants is essential for successful foresight activities. Project leaders recognized the participant invitations provided an opportunity to build expectation and raise the profile of the Initiative, given that many of those invited were also key decision makers. Invitations were accompanied by a short concept paper that presented the focal question and discussed future health related challenges. To make attendance more attractive, each invitation articulated a value proposition for the invitee, i.e., the ability to interact with other leading thinkers from the health sector and exposure to leading edge thinking.

Throughout the Health Foresight Initiative, project leaders capitalized on as many opportunities as possible to present findings to internal and external audiences. Comments and feedback received during these presentations were used to refine the communication process. Targeted communications about the Health Foresight Initiative findings will continue at Health Canada and Alberta Innovates Technology Futures throughout 2011 and 2012 to ensure that the insights and findings continue to be actively incorporated into ongoing planning processes.

4. Health Foresight Initiative Findings

Four major insights emerged from the Health Foresight Initiative:

1) Technology can empower individuals to take greater responsibility for their own health. Through personal data tracking and sharing capacities, engagement in social networks and access to health and lifestyle information on the internet, individuals are able to become proactive partners with physicians, communities of interest, and other health care service providers for illness prevention, treatment and wellness enhancement.

2) Health care professionals are now able to provide many health related services to consumers and patients any where in the world. Conversely, Canadians have unprecidented access to a vast array of health care services (and products) from outside the public funded health care system. Severing the geographic link between patient and physician is a ‘game changer’ for the Canadian public health care system.

3) The ability to interpret and act upon the increasing plethora of health related data and information will depend upon the ability of the user to validate and understand its implications. The inappropriate applications and use of data and knowledge by individuals, health care professionals and organizations is an emerging challenge.

4) Improving the health of Canadians will require the engagement and commitment of Canadian society in general. Government cannot achieve this objective in isolation.

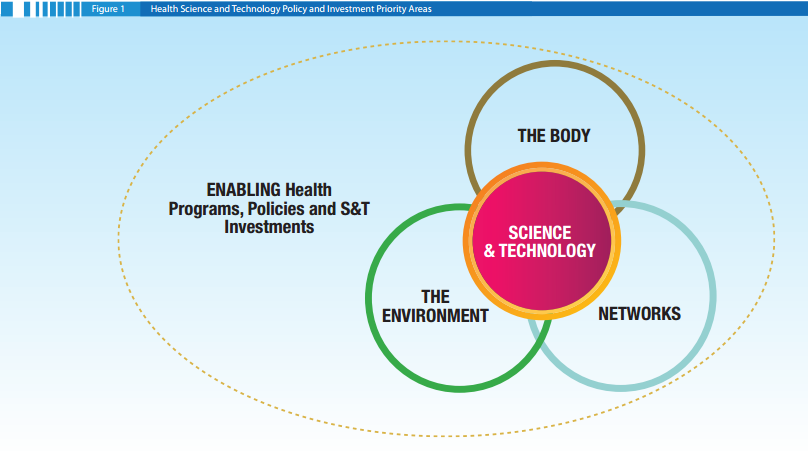

Three factors emerged as particularly significant to Health Canada and Alberta Innovates-Technology Futures during the Health Foresight Initiative; (i) the need to broaden the definition of, and approach to, health and wellness, (ii) the need to recognize the individual as a full partner in maintaining health and wellness and (iii) the paramount role of digital technologies in improving the health outcomes of Canadians. More specifically, the findings of the Health Foresight Initiative indicated that priorities must be given to investment in science and technology areas that:

• directly affect the health of the body; i.e. bio-medical monitoring devices

• enables the development and implementation of networks supporting enhanced health systems and that improve integration and sharing of health information, i.e. electronic health records.

• facilitate monitoring and analysis of environmental influences, enhances environmental quality and improves research capabilities, i.e. networked ubiquitous sensing devices for bio-medical and environmental data collection. Science and technology that integrates all three areas should become policy and investment priorities (see Figure 1). Furthermore, future health policy and investment decisions should be directed toward the creation of an enabling environment that promotes and encourages healthy living as well as the treatment of illness.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The purpose of the Health Foresight Initiative was to inform science and technology investment decisions taken today in order to improve the health outcomes of Canadians over the next twenty years. To increase the likelihood of the findings and insights being used to inform strategic decisions, the project design incorporated an iterative and integrated process of foresight engagement, innovation and communication.

This robust foresight project design fostered innovative new ideas and solution sets that are (at the time of writing) being communicated to broad audiences of health sector leaders and stakeholders for consideration. Early indications are that these findings have been positively received by key decision makers. They will continue to be incorporated into the strategic planning and decision making processes of Health Canada and Alberta Innovates-Technology Futures over coming months.