by | LIZ ALEXANDER, PhD

Futurist, Author, Consultant, Speaker

Consulting futurist, Dr. Liz Alexander, is co-founder of Leading Thought, whose clients in the United States, UK, Australia, South Africa and India look to them for ways to ‘futureproof’ their talent and organisations. She combines her futurist skills with a deep understanding of the strategic needs of business, especially as they relate to communicating thought leadership insights and paradigm pioneering ideas.

Dr. Liz is the author/co-author of 21 nonfiction books published worldwide, that have reached close to a million global readers. She contributes to Fast Company’s online platform and writes a blog entitled ‘Preparing for the Unpredictable’ for Psychology Today.

Whenever I teach creativity and innovation to groups ranging from college students to corporate executives, I begin by stressing the value of finding inspiration outside of the confines of their own disciplines and industries. The World Bank echoed that advice in their 2018 report entitled Improving Public Sector Performance through Innovation and Inter-Agency Coordination, writing:

“Understanding how other countries have tackled their public sector transformation through qualitative case studies can provide inspiration for how to go about the reform.”

Such an approach is consistent with foresight work in both looking back and more broadly in order to answer questions that the World Bank document then posed:

“What were the mechanics of solving the problem in a different country setting? What pitfalls could have been avoided? What features need to be adapted to the local context?”

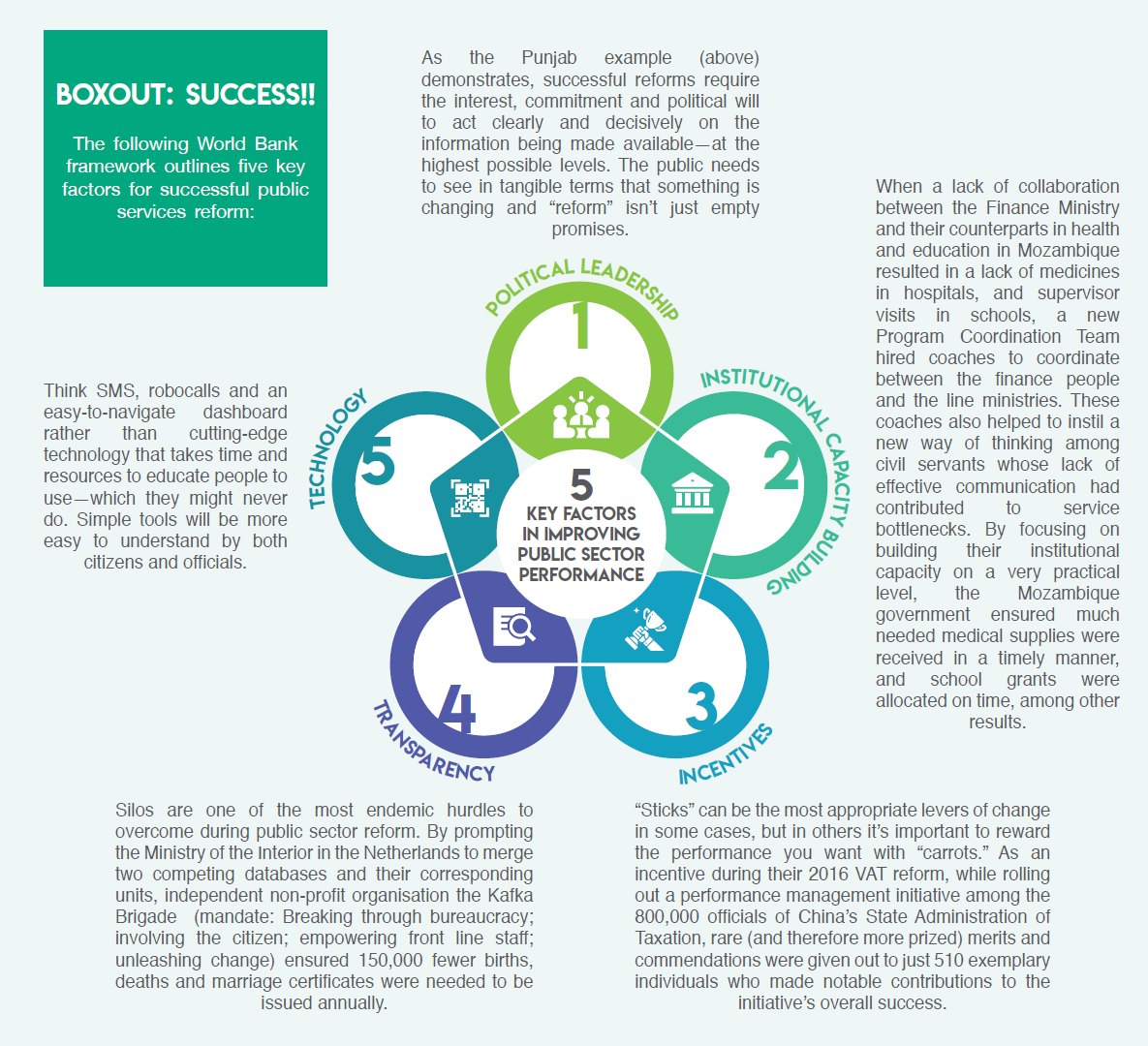

That report showcased over a dozen global case studies highlighting success factors that the World Bank identified as important for improving public sector efficiency and effectiveness (see Box Out). Three of these case studies stood out to me as illustrations of how public service initiatives have successfully reformed public sector structures, regulatory processes, enhanced productivity and front-line service delivery, not only in terms of innovative features but also altered mindsets.

Public Services Guarantee Act (PSGA) in Madhya Pradesh

It is a sad fact that the most vulnerable in our societies need many public services at one time. Even sadder is the reality in which citizens who are poor and with limited education must navigate multiple bureaucratic structures with slow-moving processes. That was the problem the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh wanted to overcome. They enacted a law—“the first act of its kind in the world”—that legally mandated the right to public services in a timely manner for its citizens, with sanctions against officials who engaged in maladministration and failed to meet the Act’s stringent deadlines.

After passing the PSGA in 2011, the state created the Department of Public Service Management (DPSM), a new structure that initiated the setting up of “one stop shops” known as Lok Sewa Kendras (LSKs). These are run by private operators who, using government-provided software, handle citizen applications for numerous public services simultaneously, then electronically forward them to the relevant departments for action. Applicants can opt to be notified of those decisions via SMS, or return to the LSK for a follow-up.

Within seven years of enacting the PSGA, the Madhya Pradesh state government extended coverage to over 400 different public services, most of which can be applied for at LSKs. The reform not only reduced the cost of front-line service delivery but also the time citizens had to spend in numerous government departments.

The PSGA is one example of how a single state can take the initiative and present a “pilot study” that others can learn from and follow. By 2018 the law had been adopted by twenty other Indian states and new services are being brought under its auspices every year. It has also helped to communicate a message that is frequently lost in bureaucratic spheres, as articulated by India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru at the inaugural meeting of the India Institute of Public Administration in 1954:

“Administration is meant to achieve something and not exist in some kind of an ivory tower, following certain rules of procedure and Narcissus-like looking on itself with satisfaction. The test, after all, is the human beings and their welfare.”

That is not to say the Act is without its detractors. One paper published in May 2019, for example, found many areas of weakness, including:

“There are no accountability norms for higher officials and elected leaders who head the public service departments…despite the provisions for financial penalty, responsible officials find ways to escape.”

In contrast, the structure of the next initiative in directly involving the chief minister and senior officials underscores the importance of strong political leadership that, in addition to performance improvements and faster front-line service delivery, enhances political reputations.