by | Liz Alexander, PhD | Futurist. Author. Consultant. Speaker.

Dr. Liz Alexander has been named one of the world’s top female futurists. She combines futures thinking with over 30 years’ communications expertise to produce publications that showcase the advice of fellow futurists on issues including the future of education, and how businesses can practically benefit from working with the futures community.

Dr. Liz is the author/co-author of 22 nonfiction books published worldwide, that have reached a million global readers, and has contributed to leading US technology magazine Fast Company, Psychology Today, and journals such as Knowledge Futures, and World Futures Review. She earned her PhD in Educational Psychology at The University of Texas at Austin.

What a difference a year makes. In the November/December 2019 issue of the Harvard Business Review (HBR), an associate professor of organisational behaviour at the Harvard Business School, together with the CEO of an organisational analytics company, published an article entitled The Truth About Open Offices. I was interested in their findings as I have always been sceptical about the claims of increased productivity and collaboration that design experts had promised and business executives hoped for. Based on real-world experiments conducted by these two researchers and others, that proved to be the case.

I mention this in relation to a recently proposed model for the future of work. Because, in a separate finding reported in that Open Offices article, these authors state that, “In general, the further apart people are, the less they communicate,” adding:

(R)emote work…tends to significantly inhibit collaboration even over digital channels. While studying a major technology company from 2008-2012, we found that remote workers communicated nearly 80% less about their assignments than co-located team members did; in 17% of projects, they didn’t communicate at all.

Their conclusion being that if you want people meeting milestones in a timely manner, remote working isn’t the answer.

Yet almost a year into the coronavirus pandemic, working from home has become a necessity for many. Rather than risk the spread of COVID19 in workplaces—especially ones designed as an open plan—more people are being asked to work from home (WFH). As someone who has done so for the past 30+ years, I’m well aware how less than ideal this is for most people in terms of their productivity, ability to collaborate effectively, and sense of isolation. Although I have no children to care for, and a dedicated, well-equipped study in which to work, I live in a condo where on-going construction noise makes it hard to listen into Zoom or Skype calls, and an upstairs neighbour’s child treats their unit like a playground or gym. Working from home isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, is it?

Yet the cover story of the November/December 2020 issue of Harvard Business Review entitled, The Work from Anywhere Future, takes WFH a step further. Written by another associate professor from the Harvard Business School, Prithwiraj Choudhury, this article and subsequent HBR podcast implies that a new working model called Work-From-Anywhere (WFA) is not only gaining ground but is suitable for everyone in an organisation from the intern to the CEO.

As with open plan offices, I decided to look beyond the hype.

What is Work-From-Anywhere (WFA)?

According to Professor Choudhury, WFA differs from working-from-home (WFH) in one significant way: “geographical flexibility.” To highlight this difference, some magazines covering the topic illustrate the text with pictures of desks strangely floating on lakes or deckchairs on exotic beaches, although HBR merely chose to illustrate Choudhury’s article with a range of architecturally varied homes! From what I gather, WFA simply means working from home anywhere in the world. You might expect someone like me, who has taken advantage of such geographical flexibility throughout my career, to be a wholehearted advocate of WFA. But it’s precisely because of that experience that I can see its many downfalls and limitations.

Let us turn back for a moment to those studies on openplan offices. As one Business Insider article (“Silicon Valley’s open offices are probably over thanks to the coronavirus—but they were always bad for employees anyway”- August 9th, 2020) pointed out, arguments against open plan offices go beyond lower productivity and increased distraction. It cited how employees “felt pressure to work longer and harder because of their lack of privacy.” How will WFA be any different?

While I have taken advantage of geographical flexibility to live in Malaysia, I still—guess what?—work from home. What this means is that when I have to jump on Skype or Zoom calls with business connections in the UK and US my normal working day goes out the window to accommodate the time differences. Luckily, this is minimal as I’m not a fulltime worker but could be hugely problematic for someone who is. Professor Choudhury believes that the difficulties of arranging synchronous meetings with team members living all over the world can be overcome by setting up an asynchronous system instead. That might work within organisations originally set up to employ people who “work from anywhere” but imagine transitioning to such an arrangement where, say, five team members live in one country and a sixth lives somewhere ten or twelve hours ahead. Isn’t it more likely that the WFA individual would be asked to accommodate the majority and be on calls and online meetings in the middle of their night?

An issue of access

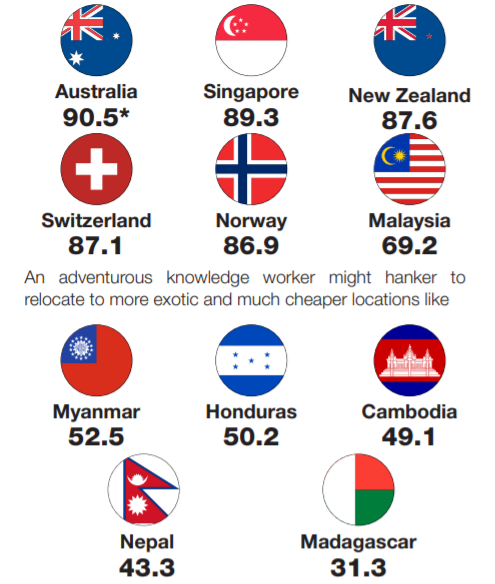

While the theory behind geographical flexibility—a rather tenuous difference between WFA and WFH—sounds reasonable, it presupposes that the countries in which the itinerant workers choose to live have robust Internet access. From the GSMA Mobile Connectivity Index rankings of 2019, I noticed that the most reliable, highly connected countries all have a high cost of living:

*denotes that country’s connectivity score.

How ‘global’ are we, psychologically?

Infrastructure challenges aside, it always fascinates me how theorists proposing new working models like WFA ignore basic human psychology. Regardless of the big, wide world we have at our disposal digitally, it appears the majority of human beings prefer to operate locally. As reported in the Global Connectedness Index 2020, sponsored by DHL and subtitled, Globalisation in a Distancing World, only 12% of Facebook friends are located in different countries to the user. Preferred online news outlets are “almost always” based in the reader’s home country as opposed to overseas sources. And 75% of Twitter followers live in the same country as the people they follow. Most notably, given the focus of that report overall, “Just about 10% of consumer e-commerce transactions in 2018 were international.”

Likewise, the workers that Professor Choudhury espouses as being the vanguard of this future trend towards WFA are the exception, not the rule. One case study he cites extensively is the United States Patent and Trademark Office. But as another article pointed out, patent examiners don’t need to coordinate much with their co-workers to be effective in their jobs. Nevertheless, in an earlier article in HBR entitled “Is it time to let employees work from anywhere?” Choudhury writes that: “We observed that WFA (patent) examiner productivity increased more if they were located within 25 miles of other WFA examiners…” working within the same technological unit. Which seems to support earlier research findings on remote working that teams work better when able to connect physically with each other, not on the other side of the world.

It’s also worth pointing out that the US Patent Office requires workers to spend their first two years at their head office in Alexandria, Virginia. They then transition into a work-from-home phase before they can fully WFA. (There’s a trust issue implied in that, wouldn’t you agree?) When they do, they must pay their own travel expenses to visit HQ, up to 12 days a year. I would certainly find it expensive and inconvenient to do that from south-east Asia. Yet such location requirements hold true for the “vast majority, 95%” of organisations willing to recruit remote workers, according to a study by FlexJobs reported by CNBC’s Make It online website, not least to comply with “employment tax law requirements.”

No panacea

Clive Wilkinson, the architect of the Googleplex, that bastion of open floor plan office space, once told Fast Company, “We’re inventing a new world, why do we need the old world?” Here’s why: You can make all the futuristic pronouncements you want, designing workspaces and imagining new work models to support them, but the vast majority of human beings are beset by “old world” psychology. While a small minority of lone wolf knowledge workers may thrive on traveling the world as digital nomads, having proven skills and talent to support such a lifestyle within an organisational culture that trusts them, most people—and their managers—prefer to be “co-located” in a place in which they can interact, formally and informally, with familiar faces. Consider how annoyed people become if someone is sitting in “their spot,” during a workshop, or how the fad for “hot-desking” caused disruptions that eroded morale and increased workplace anxiety. Most workers, like it or not, are creatures of habit who prefer face-to-face interactions, want work to be contained within a certain number of hours, and whose “geographical flexibility” is constrained by family commitments, cost of living, and access to reliable digital communications.

While Professor Choudhury posits an interesting new theory about the future of work, with the number of flaws in the WFA concept I don’t see it being embraced universally anytime soon.