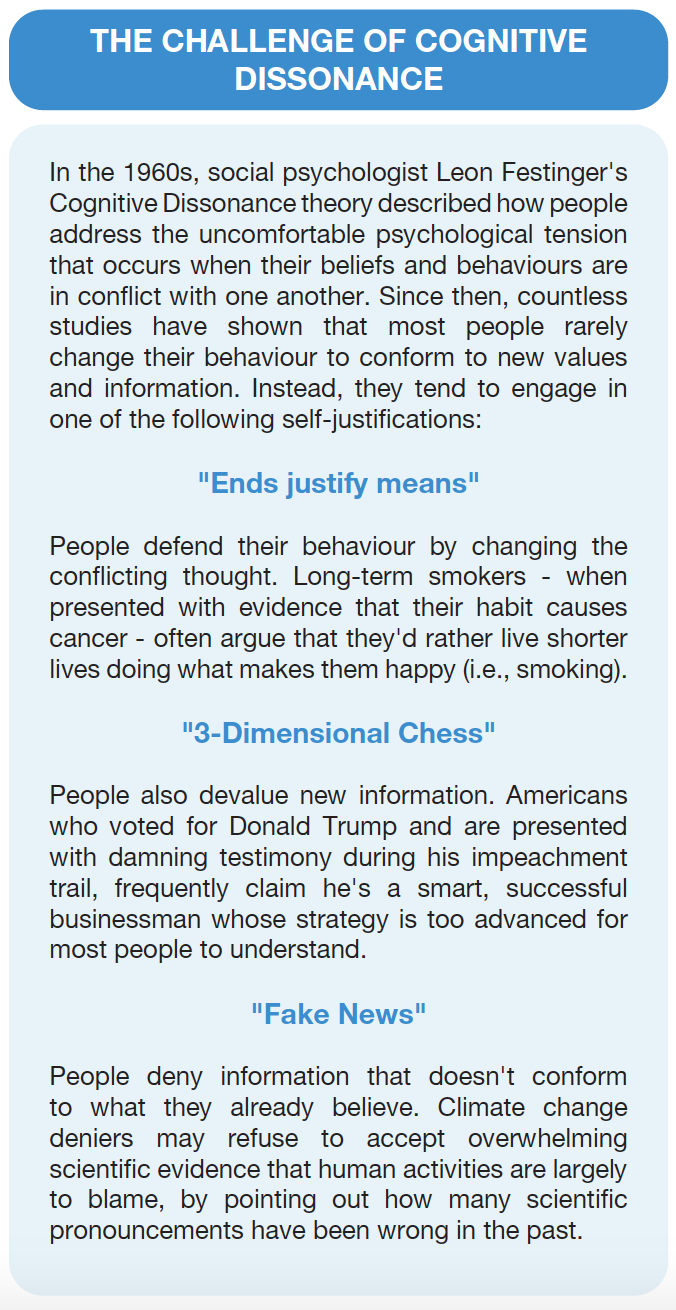

Have you ever had this experience? One described by three prominent US social psychologists in their book, When Prophecy Fails, that preceded co-author Leon Festinger’s work on cognitive dissonance:

Show him facts or figures and he questions your sources. Appeal to logic and he fails to see your point. Suppose that he is presented with evidence, unequivocal and undeniable evidence, that his belief is wrong: what will happen? The individual will frequently emerge, not only unshaken, but even more convinced of the truth of his beliefs than ever before

As a futurist I’m certainly well aware of the challenges involved in trying to encourage clients to acknowledge, let alone act on, information that contradicts their existing assumptions and beliefs. After all, Chris Luebkeman, Director of Arup’s Global Foresight, Research and Innovation team wrote in the firm’s 2050 Scenarios: Four Plausible Futures report, that future scenarios “can be comforting, disconcerting, amusing, appalling, inspirational or perhaps even depressing.”

Yet it does no good for foresight professionals to focus only on preferred futures and ignore the worst case scenarios that could end up blindsiding the organizations or government departments we are engaged to help. Since it’s our job to communicate findings that may be considered unwelcome or even threatening, many of us have become adept at finding ways to encourage our audiences to open their minds to outcomes that they might otherwise prefer to dismiss.

But before I outline some of these techniques, let me just say this: Not everyone is persuadable. Oftentimes the most intelligent, high status individuals are unwilling to change their points of view, especially when maintaining the status quo is strongly tied to their professional identities. While working in academia I met a number of experts who refused to consider new approaches because these threatened their positions as leading authorities and called into question years—sometimes decades—of work they were determined to protect at all costs.

Which is why, to become more successful at coaxing others to open their minds to new ideas and embrace uncomfortable or inconvenient truths, you first need to think like a psychologist, embrace the skills of an educator, and adopt the abilities of a storyteller.

WHO? FIRST, UNDERSTAND YOUR AUDIENCE

I’ve always been fascinated by the number and range of cognitive biases we humans exhibit, despite priding ourselves on being rational beings. But when you understand the psychology behind some of these biases, you can use them to your benefit.

Take Attentional Bias, for example. This refers to the way we pay attention to some things while ignoring or disregarding others. In the 1999 Harvard University “Invisible Gorilla Experiment,” participants had to watch a short video of people playing basketball and silently count the number of times the ball was passed between them. Midway through the game, a person dressed as a gorilla walks slowly across the court, looks directly at the camera, thumps their chest and walks off-screen. As surprising as it sounds, half the people watching the video were so focused on counting the passes they did not report seeing the gorilla.

In case you think those people were just not very observant, consider that in a 2013 study, researchers asked 24 expert radiologists to perform a familiar lung nodule detection task and inserted a large picture of a gorilla into one of the trial’s images. An alarming 83 percent of those radiologists did not spot the gorilla on that occasion, either.

It appears that when our minds are focused elsewhere, there are things—even large, unexpected ones like gorillas— we do not see. This inattentional blindness is especially common when people are already distracted. How can you use this knowledge to your advantage? Find out before you attempt to present any findings to a client or colleague what it is that’s keeping them up at night. What are their most pressing current concerns? Then look for ways to ensure your presentation addresses those concerns. That will get their attention.

Or, as Professor Matthew Hornsey of the University of Queensland advises: “Rather than taking on people’s surface attitudes directly, tailor the message so that it aligns with their motivation.” In the case of climate skeptics, for example, he says, “Find out what they can agree on and then frame climate messages to align with these .”

Remember, too, that people in positions of power and authority tend to be concerned with boosting their reputations. Making clients look good is why the next skill, common to the best educators, is also important.

WHAT? NEXT, KEEP IT SIMPLE AND RELEVANT

In a 1950 Fortune article entitled, “Is anybody listening?” business journalist William Hollingsworth Whyte wrote this oft-cited line: “The great enemy of communication, we find, is the illusion of it .”

Whyte went on to explain what he meant:

We have talked enough; but we have not listened. And by not listening we have failed to concede the immense complexity of our society and thus the great gaps between ourselves and those with whom we seek understanding.

When communicating foresight we often make the mistake of believing that what we’ve said has been heard. Lack of attention, as we just discovered, is one issue. But there is another problem that is equally important: a lack of understanding.

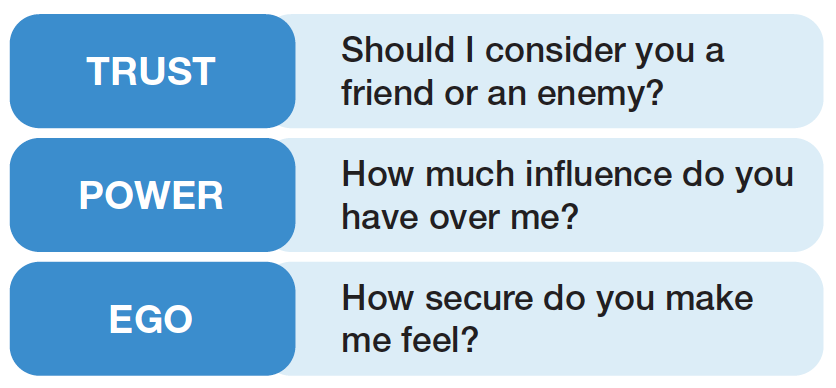

In her book, No One Understands You and What To Do About It (Harvard Business Review Press, 2015), social psychologist Heidi Grant Halvorson points to three common filters through which we are viewed by others:

My first response to the question, “How can I change my boss’s mind?” is to look for ways to make people in authority look good. Subject matter experts often assume that the information they are delivering is not only invaluable, it’s easily understood. As intelligent as our audience may be, it’s a common mistake to assume that people “get” what we’re trying to tell them. Rather than ask questions that reveal they don’t know what you’re talking about, many people in positions of power will simply dismiss your argument and refuse to discuss it further.

I once worked on a project in which the client wanted to secure a thought leadership position around future health and wellbeing. Given my love of research, I got caught up in an in-depth review of the social, demographic, technological, economic, environmental and political mega-trends and “weak signals” that would likely impact the healthcare ecosystem over the next decade. As I began rehearsing my presentation with a much wiser colleague, he stopped me in my tracks by saying, “This isn’t about how smart you are, Liz. Your job is to make your client feel knowledgeable and perceptive. But, listening to this, you’re making me feel dumb.”

At which point I completely switched my focus away from details that the client would likely find confusing and complicated—risking that they would reject the whole idea— and towards what they cared about: the bottom line benefits to their business of strategically shaping, influencing, and owning a particular industry conversation. Ever since I’ve never forgotten to ask myself: “How can I make the recipient of this information shine?”

Nevertheless, when we’re talking about outcomes that may not unfold for decades, even half a century, it can seem like a Herculean task to persuade decision-makers whose professional lives are being held to the next election cycle, or quarterly earnings, to care about something that might not even happen in their lifetimes. This is where the power of storytelling comes in—and our unique ability to mentally time travel to the future.

WHY? THEN PUT THEM IN THE PICTURE

Imagine trying to change the beliefs and behaviours of an entire country, and eventually the world. To shift a population’s long-held assumptions in order to influence them to invest in something that has never been successful in the past. Imagine that, and you have some idea of the challenge facing Clarence Birdseye in the 1920s when he tried to convince grocery outlets and shoppers to take a risk on his “frosted foods”: flash frozen fish, fruits, and vegetables. After all, before he perfected the process of flash freezing on a commercial scale, frozen food was dry, tasteless and unappealing. How was his any different?

Talking endlessly about his technological innovation wasn’t enough for Birdseye to persuade grocers and housewives to buy his frozen products. He knew he needed to tell a compelling story. Which was why early Birds Eye slogans included:

Raspberries in winter; June peas in March.

and

Modern food for modern living.

In other words, he helped to conjure up relevant pictures in people’s minds that spoke to their desires and aspirations. It was only then that the idea took off and Birds Eye foods have been known to the world ever since.

A future in which stakeholders cannot see themselves, their constituents, or their children and grandchildren living, will always just be a theoretical, empty future. That is one reason why an approach known as “speculative journalism” has been so successful at bringing to life future scenarios that mere science-based facts and hard evidence have not. It has been particularly valuable in creating emotional connections around complex topics like climate change. As the editor-in-chief of one U.S. publication reported, “We took the projections of the Fourth National Climate Assessment, interviewed scientists, pored over studies—then imagined what the West would look like 50 years from the release of the report. The result is a multi-verse of future Wests, all set in the year 2068.

None of these stories are true, but any of them could be. The fact is, we don’t really know what climate chaos will bring, but we do know that enormous challenges and opportunities lie ahead. Our chance to change the future is now, but we’ll need a better story first.

Presenting a range of different stories in which your audience can opt to play an active role will always win out over facts alone. The beauty is, well-crafted narratives do a better job of convincing others to buy into an imagined future than you can ever hope to. Because, to be honest, persuasive tactics are much more successful when people willingly change their minds on their own.

In conclusion, now that you have a clearer idea what you are up against when faced with people who are defensive, devalue, and/or deny the new information you are trying to share with them, I urge you to look upon this as a good thing—for both of you. The fact that your audience is experiencing any degree of mental discomfort shows that you have made an impact on them. As with all aspects of foresight work, none of this should be seen as a “one-shot” approach. I have always found that instead of arguing with people whose ideas appear entrenched and unyielding, it is better that I take the position of encouraging them to try and bring me closer to their point of view. This invariably opens up a long-term conversation in which each party is encouraged to find evidence that contributes to an ongoing discussion. Most people in positions of power love being challenged, as long as it doesn’t feel threatening to them. I can’t tell you how many times I have successfully modified, strengthened and eventually pushed through a mutually acceptable position—one not too far removed from what I was originally proposing—by being seen as a person willing to change her mind, rather than insisting others accept my evidence and truth.

References:

- https://www.sciencealert.com/researchers-have-figured-out-what-makes-people-reject-science-and-it-s-not-ignorance

- https://quoteinvestigator.com/2014/08/31/illusion/

- https://www.amazon.com/One-Understands-You-What-About/dp/1625274122/ref=sr_1_1_twi_2_pap?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1429033636&sr=1-1&keywords=no+one+understands+you

- https://www.hcn.org/issues/51.14/editors-note-the-case-for-speculative-journalism