by | Liz Alexander, PhD, Futurist, Author, Consultant, Speaker

We have long understood the importance of anticipating the effects of our actions because, without foresight, human beings would not have survived. However, as the 18th century French economist Frederic Bastiat pointed out, in his essay entitled What Is Seen and What Is Not Seen:

…an act, a habit, an institution, a law produces not only one effect, but a series of effects. Of these effects, the first alone is immediate; it appears simultaneously with its cause.

It is seen. The other effects emerge only subsequently; they are not seen; We are fortunate if we foresee them.

It is indeed a fortunate person who is aware of, and overcomes, the flaw in our foresight abilities that Bastiat points out. Throughout my years as a futurist, I’ve noticed that even when people are advised to think about the consequences (plural!) of their decisions, innovations, or policies, they prefer to fixate on immediate outcomes rather than the knock-on effects that may be far less desirable and harder to spot. We like to think that for every cause there is a single, ideally desirable effect. Yet, in these volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous times, such bias makes less and less sense—if it ever did.

Some years ago I developed and instructed a strategic communications program aimed at organisations ranging from Google to local government departments, on behalf of the University of Texas at Austin’s Professional Development Center, in the United States. One of the courses covered crisis communications, which was always my favourite to teach. Largely because there were so many fresh examples I could draw on, from business and industry. These involved costly, embarrassing and—worse still—trust-shattering or injurious case studies, where executives were left asking: “Who could have imagined this happening?” when they should have been questioning beforehand: “What do we imagine could go wrong with this?”

WHY ‘UNANTICIPATED?’

I’m using the term “unanticipated consequences,” raised by American sociologist, Robert K. Merton in his 1936 seminal paper, The Unanticipated Consequences of Purposive Social Action, rather than the more common and recent “unintended consequences.” Here’s why:

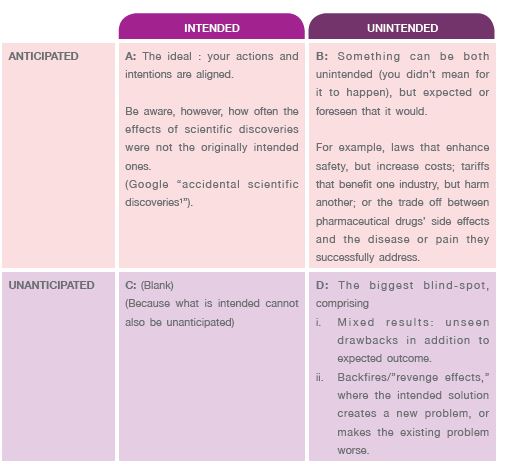

TABLE 1: ANTICIPATED AND UNANTICIPATED CONSEQUENCES

As you can see from Table 1, unintended consequences can be anticipated (B) and allowed to happen because the benefits are considered to outweigh the disadvantages. These causes also include what Merton called the “imperious immediacy of interest,” otherwise known as focusing on shortterm interests rather than long-term ones.

On the other hand, unanticipated consequences are only ever unintended (D). It is the “unseen” occurrences of D(ii) that this article will address.

As you review the following examples, consider whether you would have agreed with the official policy prescribed. What unanticipated consequences might you have foreseen?

THE COBRA EFFECT

In 19th century India, British colonial administrators were concerned with the problem of cobras. Too many of these highly venomous snakes were slithering around the streets of Delhi. Someone came up with what they must have thought was a sensible solution to cut back on their numbers: a bounty so generous that cobra hunting soon became “a thing.”

As Bastiat pointed out in that earlier quote, the first-order effect was immediate, and in line with what officials wanted to achieve. The cobra population plummeted. Problem solved? Not so fast. Because the men in charge failed to consider secondorder effects. To maintain their new income, bounty hunters began breeding cobras at home, before killing them and collecting the money. There were fewer cobras on the streets, certainly, but the costs associated with the policy had begun to spiral out of control. So the administrators did another “sensible” thing—they canceled the bounty. As the third-order effect kicked in, all those now worthless, home-raised cobras were released—you guessed it, into the streets.

In 1958, Mao’s Four Pests hygiene campaign began with similarly well intentioned ideals: decimate the populations of mosquitoes, rodents, flies, and sparrows, responsible for transmitting disease. People were especially incentivised to destroy sparrows’ nests, smash eggs, kill their chicks, and shoot the birds out of the sky, because they were also blamed for eating grains and fruits. Would you have expected this action to result in a famine? The Chinese certainly didn’t.

What was not taken into consideration was that the sparrows also ate insects, including locusts. As the sparrow population decreased, locusts proliferated. The second-0rder effect was that rice yields plunged as a consequence. The third-order effect became known as the Great Chinese Famine, in which up to 45 million people died of starvation. A cause that, on the face of it, would seem to have nothing whatsoever to do with sparrows.

Have we learned our lesson regarding the perverse, “revenge effects” all too frequently encountered when experimenting with nature? Sadly, not. A recent gene-hacking experiment conducted in Brazil, in which a biotechnology company’s intention to: “…gene-hack mosquitoes so their offspring immediately die, mix them with disease-spreading bugs in the wild, and watch the population drop off,” unfortunately, “didn’t quite pan out.”

The first-order effect was, as Bastiat proclaimed, immediate. The genetically modified (GM) males released into the wild did cause the mosquito population to originally decrease. But, within 18 months it was back to previous levels, comprising not only of wild mosquitoes but also their hybrid offspring.

The second-order, and the as-yet only speculated third-order effects, are currently a matter of dispute. Some scientists suggest “this genetic mixing could have made the mosquito population more robust—more resistant to insecticides, for example, or more likely to transmit disease,” while the bio-tech company producing the GM mosquitoes claim that it won’t.

What is not in doubt, according to population geneticist Jeffrey Powell of Yale University, quoted in Science Magazine2 is that, “something unanticipated happened.” Adding, “When people develop transgenic lines or anything to release, almost all of their information comes from laboratory studies. Things don’t always work out the way you expected.”

But why is that the case, so often, when there is ample historical precedence to guide current and future decisions? When European settlers brought wild rabbits to Australia and New Zealand in the late 19th century, to provide food, sport, and “a touch of home,” those countries ended up with a population explosion of these pests that devastated the local ecology. When the invasive plant called kudzu was introduced into the United States around the same period, it ended up with the nickname “the vine that ate the South.” The U.S. continues to have to deal with the economic, cultural and environmental effects, costing hundreds of millions of dollars every year, because of kudzu infestation. We know from past experiences the deleterious effects of such “unforeseen” decisions—but pursue our own then act surprised when something “unexpected” occurs.

As Robert K. Merton outlined in his above-mentioned paper, ignorance is a key cause of unanticipated consequences. Not because the people involved aren’t intelligent, but because of having, “insufficient or inexact knowledge of the many details and facts needed for a highly approximate prediction of consequences.” A look back in history might help.

DISREGARDING HUMAN NATURE

It’s not just the complexities of natural ecosystems that are responsible for so many unanticipated consequences, but something you’d think we’d all have a greater understanding of by now: basic human nature.

Perhaps you, too, have had to endure open-plan work spaces. Maybe you’ve even championed them? Indeed, the expected benefits were never in dispute: greater collaboration, leading to increased productivity and enhanced creativity, being among them. Yet many studies have found that the majority of employees heartily dislike the trend for “open architecture,” which has been proven not to work—literally3.

We may be social creatures but we’re not like bees or ants—we like our own space and to choose who we have to interact with. Paradoxically, open offices were found to decrease the amount of face-to-face interactions by some 70 percent, prompting virtual contact like emailing and instant messaging to go up4. Employees will often wear headphones to tune out all the noise and distractions that lead to overstimulation in large open-plan areas; they report greater employee dissatisfaction because of the lack of privacy and the feeling they are constantly on show. In extreme cases they will even leave their jobs.

As Edward Tenner– the man who coined the term “revenge effects”—wrote in his 1997 book, Why Things Bite Back: Technology and the Revenge of Unintended Consequences, “Whenever we try to take advantage of some new technology, we may discover that it induces behaviour which appears to cancel out the very reason for using it.”

As Edward Tenner– the man who coined the term “revenge effects”—wrote in his 1997 book, Why Things Bite Back: Technology and the Revenge of Unintended Consequences, “Whenever we try to take advantage of some new technology, we may discover that it induces behaviour which appears to cancel out the very reason for using it.”

Another of Merton’s factors is what he calls “error,” including the belief that old habits will still apply to new situations and nothing will change. Yet the more sensitive car alarms have become, the more people tend to ignore them; Smartphone use has led to an uptick in automobile deaths and injuries, because people are texting or talking while driving—something they never used to do; self-driving cars kill pedestrians5 because their software was not designed (by humans, presumably) to know that people tend to wander across roads wherever they feel like it—and not just where they should.

YOU WON’T GET WHAT YOU IGNORE

For our final example, let’s take a look at a piece of federal legislation.

The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) that went into effect in the United States in 2002 was certainly well-intentioned. Who would argue against improving students’ basic competencies in reading and mathematics, after all? Rankings in which the U.S. had fallen way behind countries in Asia and Europe. How could this education reform have harmed the very students it was designed to help?

Another “error” Merton identified in his 1936 paper was “wish fulfillment,” in which “only one or some of the pertinent aspects of the situation which will influence the outcome of the action, are attended to.” One factor that appears to have been ignored with this particular legislation, something well known to parents and employers, is that you get what you reward. For example, I’ve seen this countless times within organisations that say they are committed to team-building and collaboration, yet whose incentives are directed towards rewarding individual work.

In the case of the NCLB, one of its key “innovations” was to link standardised testing to punishments, including decreased funding for schools and even closures. So—no surprise, surely?— teachers went ahead and taught only what was needed for their students to pass the exams. Yet, according to the National Education Policy Center at the University of Colorado, Boulder, cited in a March 2015 Business Insider article6, “… there is no evidence that any test score increases represent the broader learning increases that were the true goals of the policy. Goals such as critical thinking; the creation of lifelong learners; and more students graduating high school ready for college, career, and civic participation.”

So, while the goal was to level the playing field for struggling students in comparison to their more advantaged peers, the NCLB largely did not achieve that. Before I share what I think are some simple, immediately implementable tools that might have helped change that negative outcome, I would say generally it’s better to clearly state what you do want to happen (Every Student Succeeds—the reform that replaced the NCLB in 2015), than what you don’t (No Child Left Behind)

A SIMPLE QUESTION

There is a host of proven, robust foresight tools that groups can use to reduce the risk of unanticipated consequences. Scenarios and STEEP-V are just two that spring to mind. But something even quicker and simpler, I believe, could help significantly reduce the number of unforeseen effects that happen in technology, business, social action, and government.

In a Fast Company article I wrote entitled Three Ways to Unlearn Old Habits Faster7, on the topic of lifelong learning, I quoted Richard Feynman, joint winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965. He described how he navigated the doubt and uncertainty of scientific exploration this way: “We are trying to prove ourselves wrong as quickly as possible, because only in that way can we find progress.” I suggest that anyone wishing to improve their ability to foresee the second, third, and even fourth-order effects of their actions, that otherwise would remain “not seen,” might ask themselves, “How could we be wrong?” in assuming that later, less desirable knock-on effects, won’t occur. Then actively seek out evidence that challenges the “immediate effects only” assumption.

The default for most people, however, is to do the opposite: known as confirmation bias. Sadly, we are too inclined to want to prove ourselves right. Which is why, 200 years after Bastiat wrote his treatise on foresight, it appears only a limited number of “fortunate” individuals still do the hard work of thinking, in order to foresee what others can’t.