by | Liz Alexander, PhD

Futurist, Author, Consultant, Speaker

In Orson Scott Card’s award-winning sci-fi novel, Ender’s Game, six-year-old Ender Wiggin spends three years at Battle School, orbiting high above the Earth, where he trains to one day fight a telepathic alien race that threatens to destroy humanity.

Whilst playing digital games, Ender demonstrates considerable strategic genius. He heads a team of children that’s always at the top of the leader board. Even faced with impossible odds in the final battle, Ender and his group destroy the aliens completely. The twist in the tale is that Ender was never playing simulated computer games at all; every conflict against Earth’s enemy was real.

Outside the realm of fiction, however, video gamers aren’t much admired, or encouraged. One online article I read claimed that their obsession resulted in “poor social skills, time away from family, schoolwork and other hobbies, lower grades, reading less, exercising less, becoming overweight, and having aggressive thoughts and behaviours.” But just how true is this? Do the computer game-based skills that Ender Wiggin developed—team building, collaboration, risk-taking, strategising, and moral decision-making—occur outside the pages of a novel? Considerable evidence suggests that they do.

Let’s look at the connection between playing video games and three attributes I assume any society would wish to develop in its youth: resilience; cross-disciplinary problem-solving; and spatial skills related to STEM success.

Resilience, Anyone?

In the opening parapgraph of his essay, The Morals of Chess, American polymath Benjamin Franklin writes:

Franklin goes on to list foresight, circumspection, caution, and “not being discouraged” as four important by-products of playing this particular game. Nowadays, we tend to use the term resilience for “not being discouraged.” Substitute Super Mario, World of Warcraft, or Halo 4 for the game of chess and the same argument applies. Resilience in the face of failure is one of the motivational advantages outlined by the Dutch authors of a paper entitled, The Benefits of Playing Video Games , published in the journal American Psychologist. They refer to Professor Carol Dweck’s theory that posits how children see their level of intelligence as either fixed (cannot be changed) or incremental (improves with effortful persistence). By earning points, acquiring more valuable tools, and gaining admittance to advantageous guilds or other teams, these authors argue that, “…video games are an ideal training ground for acquiring an incremental theory of intelligence because they provide players concrete, immediate feedback regarding specific efforts players have made.” In short, trying and failing, then trying different tactics next time—the very challenges inherent in complex video games—can help motivate players to adopt an attitude of persistent optimism that’s beneficial in both school and work contexts.

Solve For X

Unfortunately, the doom-and-gloom critics of video games and the people who play them, have helped to embed into the public consciousness an image of the pasty-faced, obese teenager slumped over his or her computer for hours on end. But as the Dutch authors of the article mentioned earlier point out, video games have, “…changed dramatically in the last decade, becoming increasingly complex, diverse, realistic, and social in nature.” And their article is now almost ten years old!

Consider the title of the book written by the Institute of the Future’s Director of Game Research and Development, Jane McGonigal : Reality is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. That is not mere hyperbole when you consider that today’s digital games offer more than just opportunities to virtually kill one’s enemies, whether alien or human. Here are a few examples of how they can help address some of the most pervasive problems we face today:

Spatial Skills and Stem

“Contrary to conventional beliefs that playing video games is intellectually lazy and sedating, it turns out that playing these games promotes a wide range of cognitive skills,” continue the Dutch authors of the aforementioned American Psychologist journal article. In a section entitled, Cognitive Benefits of Gaming, they point to the way in which ‘action games’ in particular help players to develop focused attention and hand-eye coordination more quickly than academic courses aimed at enhancing these same skills.

Why is this important? The authors cite a 25-year longitudinal study linking superior spatial skills with greater achievement in those academic areas we refer to as STEM: science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. As one quoted cognitive neuroscientist states, “Video games are controlled training regimens delivered in highly motivating behavioral contexts . . . because behavioral changes arise from brain changes, it is also no surprise that performance improvements are paralleled by enduring physical and functional neurological remodeling.” Once someone’s brain has been remodeled in such a way, they then have the capacity to apply that advantage to other contexts.

A Necessary Balance

Let’s not confound these highly popular, motivational, and skills-building games with what we’re seeing happen with a lot of our infants today. As one new Japanese study points out, too many parents place an iPad into the hands of one to four year-olds, in order to keep them occupied and amused. Children that young do not benefit from so much screen time and constant stimulation. Instead, they tend to suffer delays in speaking and overall language ability, as well slower development of important motor skills and social skills.

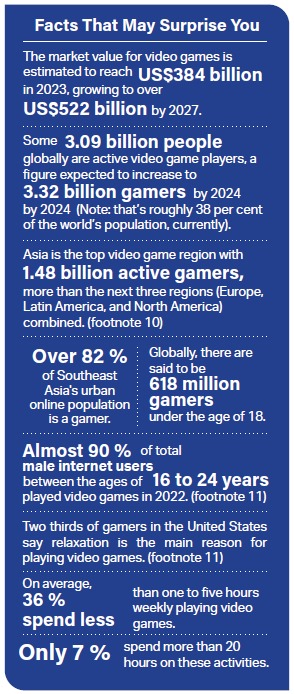

On the other hand, youth—the majority of whom are not spending as much time playing video games as detractors often claim (see Boxout)—develop many of the cognitive, emotional, motivational, and social skills now being studied in more detail by academic researchers.

Perhaps we should ask ourselves what more we can do to incorporate games design into projects aimed at encouraging greater youth engagement. Perhaps the problem lies not so much with video games per se—which are obviously highly engaging and motivational to people of all ages across the world—but why we are not designing reality to better match these online experiences.