by | Dr Muhammed Abdul Khalid

Dr Muhammed Abdul Khalid is currently a Senior Associate at MIGHT. He is a Research Fellow at IKMAS, UKM and Adjunct Professor at CenPriS, USM. He is formerly the economic advisor to the prime minister.

The future of labour force in Malaysia in the context of 4IR, with a focus on older persons.

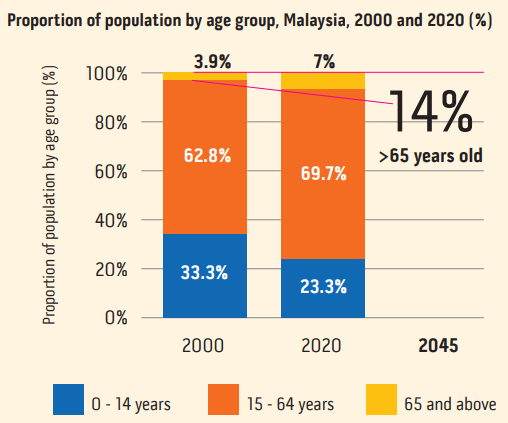

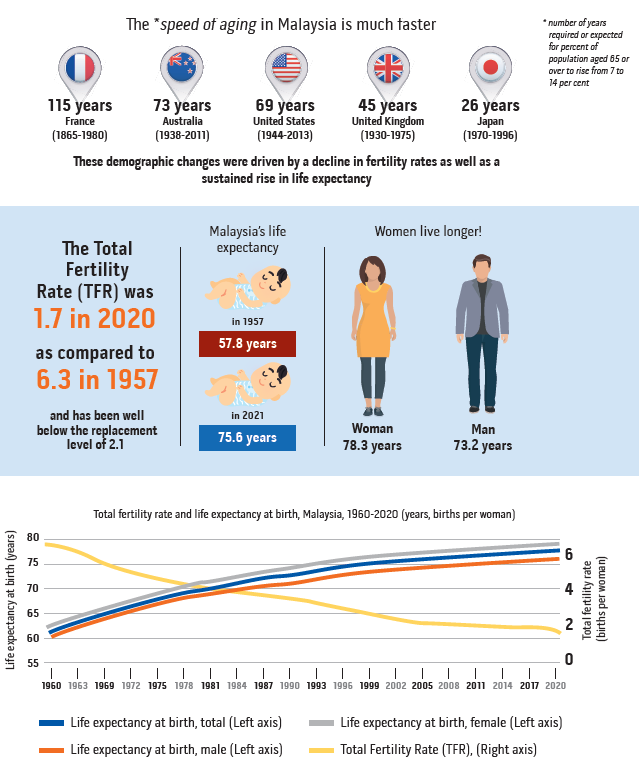

Malaysia is speedily aging compared to other countries

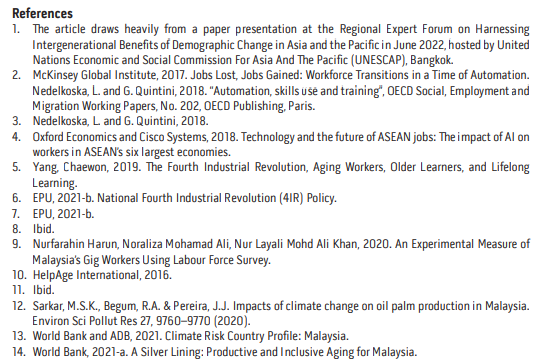

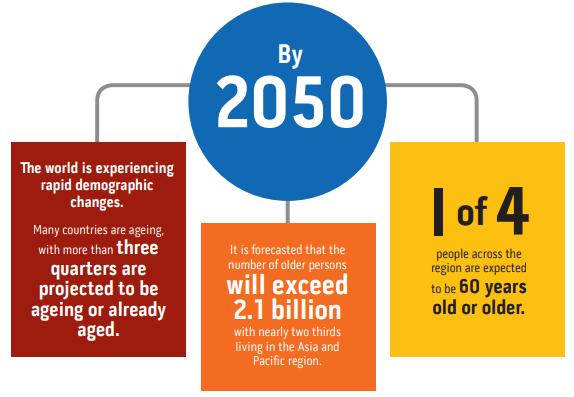

These demographic shifts will require changes in the labour market since the share of prime-working age adults will be declining, hence increasing the need for older persons to participate. In 2020, older persons make up 7% of the population.

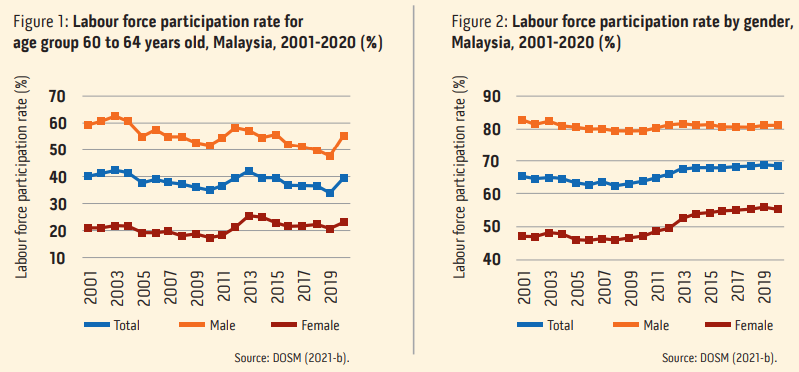

Despite the increase of older persons in Malaysia, the participation rate of older persons in the labour market remains low. The labour force participation rate (LFPR) in Malaysia for those aged 60 – 64 in 2020 at 39.2 percent islowercompared to the overall (and increasing) LFPR at 68.4 percent (Figure 1). The increase in overall LFPR from2001 to 2020 is due to a higher participation of women in the labour force (Figure 2). Meanwhile, the share of those aged 55 and above in the labour force increased marginallyin the last ten years, from 6.6 per cent in 2010 to 8.7 per cent in 2020.

Population ageing will increase pressure on government fiscal resources, particularly on healthcare and pension systems. A lower working-age population and increased number of older persons tend to reduce revenue collection, and hence increased pressure on public finances to overcome the increasing demand on pensions and healthcare. In addition, the access and coverage of oldage social protection retirement schemes remains small, with sizeable future retirees possibly to retire in poverty. Increasing health issues will also increase pressure on Malaysia’s healthcare system and pensions. Although older persons are bolstered by familial and community support, this care system is declining.

The current labour market outlook for older persons in Malaysia will be challenging due to key emerging trends, namely the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) and environmental and climate change. The Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), one of the biggest trends impacting the future of employment, will result in a shift in the existing jobs and require more complex skills from the workforce. While 4IR has the potential to raise income levels and improve quality of life, with about 590 million to 890 million new jobs having been estimated to emerge from 4IR especially for those who have digital access, it can also bring greater inequality because of its potential to disrupt labour markets. Job markets are increasingly segregated into ‘low-skill, low-pay’ and ‘high-skill, highpay’ segments. It is estimated that 400 million to 800 million jobs worldwide will be displaced by 2030 because of global automation and 14 per cent of existing jobs will become redundant in the next 15 – 20 years. About one in three jobs will change in response to automation, and a sizeable number will be replaced and become obsolete. By 2028, approximately 28 million fewer workers in six ASEAN member countries (Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand, Philippines, Malaysia, and Singapore) will be needed to produce the same level of output asin 2018. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has estimated that 14 per cent of existing jobs will become redundant in the next 15 to 20 years while 32 per cent will change in response to automation. Projections estimate that by 2028, 0.5 million less people would be needed to produce the 2018 level of output for Singapore, 1.2 million less for Malaysia and 4.9 million less for Thailand due to advances in technology. Therefore, workers will need to periodically upskill and reskill to cope with technological shifts or enhance skills which cannot be highly replicated by machines. In 4IR, the most emphasised competences are adaptability and self-directed learning and thinking. For older workers, it is pertinent to engage in lifelong learning to cope with advances in technology.

Malaysia has several policies in place, such as the 4IR National Policy and Malaysia’s Digital Economy Blueprint, to take advantage of 4IR which is expected to increase labour productivity in Malaysia by 30 per cent. 4IR is expected to increase labour productivity across all sectors, with improvement in agriculture by 55 per cent, manufacturing, 30 per cent and services, 45 per cent by 2030. Government estimates that 4IR is expected to create up to 500,000 jobs by 2025. Under the 4IR policy, Malaysia is planning to transform 20 per cent of semi- and low-skilled labour to highly skilled labour that will engage in 4IRrelated industries. Three out of the five initiatives that focus on talent in the 4IR National Policy are related to schools and higher education institutions. These initiatives are geared mostly for young graduates and not older workers. For example, the MyDigitalWorkForce in Tech (MYWiT) programme providescompanies with training incentives to hire fresh graduates and unemployed Malaysians in 4IR-related sectors. However, there is no specific provision for older workers.

It is important to ensure that while pursuing 4IR, workers must also have access to social protection and social assistance. While labour participation in the gig economy and in digital platforms in Malaysia has been increasing, workers lack access to benefits and social security usually afforded to traditional employment. About 559,900 persons were involved in Malaysia’s gig economy in 2018, with roughly 1 in 10 or 50,700 aged 55 – 64. The incidence of gig work increased during the pandemic because workers had to supplement their income due to pay cuts and job losses. However, gig workers, like other categories of informal workers, face challenges in enjoying social protection, skills development, or social support.

The negative impact of environmental and climate change will also affect the labour market, and in particular towards sectors like agriculture and tourism. Evidence suggests that older persons are more vulnerable to the effects of temperature extremes and have a significantly higher mortality risk in extreme temperature events due to susceptibility of disease, reduced mobility and the effect of stress. Increased incidences of drought and flooding on rice growing could reduce yields by up to 60 per cent. Drought can also result in an inability to cultivate other valuable crops for Malaysia such as rubber and palm oil. Climate studies suggest that palm oil is very vulnerable to climate change, with large areas of the country likely to become unsuitable for cultivation. Although 10 per cent of the labour force is in agriculture, the incidence of older workers in agriculture is the highest among all age groups, at 25.5 per cent, which makes them more vulnerable to climate change. Tourism in Malaysia too will be affected by climate change due to ecological changes, flooding, coral bleaching, and extreme heats. It will impact tourism sites; besides extreme heats will lead to personal discomfort and potential health problems. Pre-pandemic, tourism and hospitality industry contributed about 16 percent to GDP and making up just under a quarter of all employment, or about 3.5 mil workers.

Several policies and strategies can be deployed to promote active participation of older persons in the labour market, including reducing age discrimination and promoting gender and age-friendly practices in workplace, with many older persons still experiencing or perceiving age discrimination in their workplace.

Anti-age discriminatory laws can be introduced or further refined to ensure older persons are not discriminated against in the labour market. Flexible working settings and gender and age friendly workspaces can also enhance the hiring and retention of older workers that are more highly educated, especially in urban areas. Expanding upskilling and reskilling programmes for the older workers is vital. Current interventions are limited, both in size and scope. A dedicated skills-building initiatives for older workers, particularly those with relatively low level of education and skills are needed. Widening incentives for employers, in particular towards recruitment of aged workers is one of many efforts in rewarding employers who employ and retrain elderly workers. Malaysia has less specific and non-extensive incentives for the recruitment of older workers, with tax deductions are fairly limited in size. Singapore’s experience is useful, as it has implemented various programmes to enhance employability of older persons, such as employment credit, and grants are provided to employers who employ older workers. Adjustments need to be done to ensure pensions and contributory systems are in line with the ageing population, in particular to ensure all workers are covered by social protection and social insurance as early as possible, without differencing their employment status (formal sector vs informal sector) or nationality (citizens vs migrants/ refugees/stateless). Enhancing female labour force participation is equally important, with flexible working time arrangements that would enable women to balance societal expectations or the perception that women would need to shoulder housework responsibilities. Strengthening the affordability, accessibility, and quality of care options could promote more women employment by alleviating them of the extra burden of childcare. More generous parental leave policies that includes paternity leave could also support female labour force participation. Finally, promoting elderly health in the workplace is crucial. Policies that promote healthy ageing and improve safety in workplace by integrating age and gender in workplace risk assessments would encourage better labour force participations of older workers.